'One of the 20th century's great artists'

Avant-garde, surreal, gothic - who would have thought cartoonist Walt Disney had such a dark side?

By Jonathan Jones

Thursday November 9, 2006

The Guardian

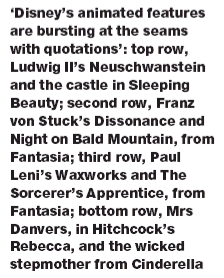

Walt Disney warped my mind. It was the first time I visited a cinema, to see Sleeping Beauty. That forest of thorns enveloping the castle has haunted me ever since; in my dreams for years, a great chasm opened up before the prince, an impossible yawning space full of spikes and twisting briars. Last night, I watched it with my daughter. What will it become in her mind? It felt like passing on a folk tale by the fire, and yet some people are wary of exposing their children to the genius of Disney.

I don't need to labour the vilification of the man, who died 40 years ago this Christmas. No other artist's signature appears on the products of an industry that is the cultural equivalent of Coca-Cola or McDonald's, and to many people, buying a toy Pinocchio is as bad as feeding your child burgers. Marc Eliot's 1993 biography branded Disney an FBI informant union-basher, and hints at worse. In a classic episode of The Simpsons broadcast shortly after Eliot's book came out, Bart and Lisa watch a corporate propaganda film at Itchy and Scratchy Land that says animation pioneer Roger Meyers Sr "loved almost all the peoples of the world" - an apparent swipe at Disney's alleged anti-semitism. Hating Disney has become a cliche. A few months ago, the over-rated guerrilla artist Banksy left a figure of a Guantanamo prisoner at Disneyland - where else? - as if Walt, who died in 1966, was directing the war on terror from his cryogenic vault.

When a long dead cartoonist and film-maker is reviled for the crimes of the present administration, something is out of whack. Walt Disney was one of the great American artists of the 20th century. This needs to be recognised. So here I am, Walt, coming to the rescue, aided by an exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris that celebrates Disney's films as visual art.

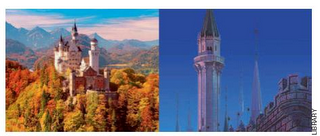

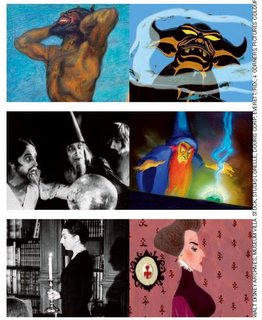

Yes, I know: to call Walt Disney a great artist begs a couple of questions. Even his authorship of the mouse he drew in 1928 in his career-making cartoon, Steamboat Willie, has been questioned. As soon as Disney started making money, he hired teams of designers and animators. Obviously he wasn't Nick Park, doing it all himself. He never claimed to be. He was a modern artist, an American artist - and far from ignorant about the avant-garde. Salvador Dali's original paintings for an unfinished collaboration with Disney, a film called Destino, are on view at the Grand Palais. They point to a film that would have been as remarkable a meeting of Hollywood and the avant-garde as Dali's sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound.

This is not in the least surprising. Disney's films abound in stupendously imaginative metamorphoses, sublime fantasies to rival any surrealist painting. Disney anticipated - and surely influenced - Andy Warhol in turning his studio into a collective enterprise, a factory. He ruled over his cartoonists with an iron fist. Yet when it comes to authorship, the analogies with Warhol, or Marcel Duchamp, are not really necessary. You only have to watch a few Disney films, widely separated across the decades of his career, to recognise the consistent obsessions that can only have been the product of one man's mind.

In 1929, only a year after Steamboat Willie made Mickey Mouse a star, Disney created a cartoon that could not be more different. Skeleton Dance is American, deeply so, in the vein of Washington Irving and Edgar Allan Poe - a jazz-age honk of American gothic that brilliantly uses black and white silhouettes to create an archetypal midnight churchyard where the skeletons get out of their graves and dance. When Tim Burton does this sort of thing, it's hailed as a gothic subversion of the homeliness of Disney, but Disney subverted himself first. When later he came to make Fantasia, the skeleton dance was echoed in the march of the mops carrying their buckets of water until Mickey chops, chops, chops them up.

Walt Disney's imagination is macabre, as well as delighting in innocence. You could even say that far, from providing generations of children with innocent escape, he filled their minds with darkness - which somehow, in the hands of critics, becomes a fault. In fact, it proves that, beneath the all-American facade, Walt Disney had a terrible secret: he was a true artist.

What strikes you, looking at his films, is not simply the consistent thread of ideas and images and ways of telling a story, but the unexpected nature of this personal style. It's not the routine comic stuff, the escapades of Donald and Mickey, that is inimitable hardcore Disney. Few people find Donald Duck as funny as Bugs Bunny. Disney wasn't a humourist. Again and again, it is the dark side of the Disney landscape that you know him by, from the early black and white Egyptian Melodies, in which a spider crawls down a highly realistic tomb shaft beneath the Sphinx to be terrified by the spectacle of mummies having a midnight party, to the skull-shaped island, inspired by King Kong, in Peter Pan.

Disney's supreme achievement was to give visual reality to the fairytales of the Europe that Americans growing up in the 1930s and 40s no longer knew, as their immigrant parents had. Of course, we can buy the original transcripts of peasant tales by the Grimms or Charles Perrault, or read retellings by Angela Carter. Yet Disney reached into folklore, grasped its essentials, and represented it for the modern child. When it comes to Snow White, can anyone separate the folk story from Disney's version?

Here we come to the one accusation, the one dilemma that really counts. Is Disney good or bad for children? Do the studio's versions of classic stories do them justice? An adult fan of the fairytale might sit down and watch Sleeping Beauty or Cinderella and be appalled by the interpolated characters and dated graphic styles, and see in all this Disney's true crime, the cosying - indeed the "Disneyfication" - of traditional stories.

One answer is:watch with a child, see the wonder on a little face. But sadly, kids like the Tweenies, too. What do they know? However, watch more closely, watch the films as art, and surely the truth becomes obvious. Disney changed the letter of the fairytale but saved its spirit. The forest of thorns that scared and amazed me in Sleeping Beauty is one version of the encounter with evil, death and terror that is at the heart of all his fairytale films, once the viewer has been lured in by the sugar candy coating. The nightmare spirit of the fairytale that psychologist Bruno Bettelheim defended is all there.

What Disney actually achieved was not to diffuse an American banality worldwide but, in a world that was becoming ever more banal and forgetful, to preserve the old oral storytelling of the pre-industrial world. Few artists have done as much as Disney to humanise modernity; the magical proof of this is one of his last films.

If you still subscribe to the cliche of Disney as a propagandist of cosy Americana, consider this. There was one Disney film I didn't intend to mention because I assumed it must have been made by the studio after he died or retired - it seems so remote from everything we "know" about him. In fact, even hostile biographers acknowledge this magical, and totally unAmerican child's-eye vision of London as one of the films on which he lavished most attention, a film he was obsessed with making for 20 years, and turned into his final testament. If you want to know the real Walt Disney, watch Mary Poppins.

No comments:

Post a Comment