A WIFE LESS ORDINARYPicasso’s wife Jacqueline has always been a mysterious figure. Now her close friend has shed light on the legal battles and turmoil that led to her suicide. John Follain reports

Pablo Picasso was 72 when he first set eyes on Jacqueline Roque, a green-eyed beauty 45 years his junior, in the pottery where she worked on the French Riviera. He wooed her for six months, drawing a giant dove in white chalk on the wall of her house, and married her in secret before spending the last 20 years of his life with her.

Picasso painted and drew Jacqueline hundreds of times; her features, albeit stylised, are instantly recognisable in a vast swathe of the Spanish artist’s prodigious output. And yet little is known about her. Jacqueline is herself in part to blame for this. The most reclusive of Picasso’s loves, she liked to say of him: “You don’t cast a shadow over the sun.” When she did step out of the shadows, in an acrimonious seven-year battle over his legacy, she was attacked by his other heirs as a possessive, moneygrubbing figure who went so far as to hold her husband hostage.

Twenty-one years after Jacqueline committed suicide in 1986, a close friend who was her privileged confidante has written the first portrait of this self-effacing muse. Pepita Dupont, a journalist with Paris Match magazine, befriended Jacqueline in 1983; an exhibition of Picasso’s works, including many portraits of Jacqueline, prompted her to write to his widow. Notoriously shy of the media, Jacqueline hesitated for six months before inviting Dupont to her Notre-Dame de Vie mansion near Mougins, north of Cannes. Jacqueline gave her a tour of the hilltop mansion and the treasures in its 35 rooms, and the women became friends.

Dupont decided to write The Truth about Jacqueline and Pablo Picasso after visiting the Picasso Museum in Paris on its 20th anniversary, in 2005. “The only sign that Jacqueline had ever existed was a small portrait of her in a notebook of sketches, but her name wasn’t mentioned. And this panel thanked members of Picasso’s family, but she wasn’t on it. But if it wasn’t for her, the museum wouldn’t even exist!” exclaims Dupont. A diminutive figure with big, almond-shaped eyes, long black hair and a dignified bearing, Jacqueline suffered two family tragedies even before she reached her twenties. Born in 1926 in Paris, she was only two when her father abandoned her mother and her four-year-old brother. Jacqueline never forgave him. Her mother raised her in a cramped concierge’s lodge near the Champs Elysées, working long hours as a seamstress. Jacqueline was 18 when her mother died of a stroke.

After finding work as a secretary, Jacqueline married André Hutin, an engineer, in 1946. She gave him a daughter, Cathy, and followed him to west Africa, where he worked on a railway line. But after four years there, she found out he was having an affair; she filed for divorce and settled on the French Riviera, working as a sales assistant at the Madoura pottery in the village of Vallauris, where Picasso made ceramics.

When Picasso met 27-year-old Jacqueline there in 1953, her features reminded him of the young woman holding a hookah in Delacroix’s 1834 canvas Femmes d’Alger dans Leur Appartement. He fell in love with her on the spot and courted her assiduously. She was wary of committing herself. “I knew about his reputation as far as women went. Pablo was old enough to be my grandfather,” she confided later. “I’d just had a painful divorce, and I had Cathy.”

Picasso pressed on regardless. He brought her a red rose every day, wrote poems for her and told her he had waited until his old age to find out what love really was. After six months they became lovers. When Dupont asked Jacqueline why he fell in love with her, the first reason she gave was that he was fascinated by her innocence and honesty. Jacqueline said of herself that she had been so ignorant about sex, she only realised afterwards how she had become pregnant by her first husband. “ But Jacqueline was very sensual, and with Picasso the chemistry was immediate. There was a strong complicity, love and eroticism. And in her, Picasso found all that a man seeks in a woman: she was at the same time his mistress, his mother, his sister, his accomplice and his muse,” says Dupont.

Given Picasso’s track record with women – biographers attribute seven main loves to him, but he is believed to have had many more affairs – Jacqueline sought to lay down the law early on. She warned him: “You have to know that if one day there is another muse, I’ll congratulate her, I’ll send her flowers. But I’ll be out the door.”

Jacqueline wasn’t jealous of his former conquests. How could she be, she said, given that he was 72 when they met? She willingly prepared cheques for him to sign every month for former girlfriends. “When women lose their beauty, life is pretty cruel,” he told her.

For more than three decades before meeting Jacqueline, Picasso had been separated from his first wife, Olga Khokhlova. As Franco’s Spain banned divorce, it was only after Olga’s death in 1955 that Picasso became free to marry again. He married Jacqueline in secret in Vallauris village hall in 1961, with his lawyer as best man and a surprised cleaner as the only witness. The newlyweds celebrated that evening with a dinner of duck and champagne, after which Picasso, who couldn’t stay away from his studio for long, went to paint a small canvas he dedicated to “Jacqueline, my wife”.

The marriage incensed Françoise Gilot, who had left Picasso after 10 years in 1953, accusing him of abusing her and of infidelities. As revealed by her letters to him, she had been hoping to re-conquer him one day. Her hopes dashed by the marriage, Gilot threatened to publish a memoir unless he handed over £200,000. He agreed to give £100,000 to each of their children, Claude and Paloma, according to Dupont, and Gilot promised to abandon the project. But she went ahead anyway, publishing an unflattering account called Life with Picasso.

From early on in their relationship, Picasso painted and drew Jacqueline many times – but she virtually never posed for him; she was simply there, in the house with him. She was the only love he tolerated in his studio when he was painting. He worked with such intensity, she said later, that his gaze was “like a laser beam”; nobody could pass between him and his canvas. She would stay up all night to watch him paint. He would scribble his love for her on the back of his canvases; messages such as “For Jacqueline’s Saint Valentine’s Day”, or, on her saint’s day, “For Jacqueline, for her day, her husband”.

The two were so close that she rarely strayed from their home – they lived in the 17thcentury castle of Vauvenargues at the foot of the Sainte-Victoire mountain near Aix-enProvence, and then in the hilltop mansion at Mougins. He was so worried about her that whenever she had a bath he would come, brushes in hand, to check she hadn’t drowned.

Picasso could also be cruel to her, so much so that Jacqueline sometimes called him “the abominable snowman”. She left hospital once after an operation, a drain still inserted in her body; she was supposed to rest, but instead she went with him, at his insistence, to a bullfight. But he was not the miser depicted in several biographies; Jacqueline insisted that he had never paid for a restaurant meal by drawing on a tablecloth. For years he met all the medical expenses for the treatment of his estranged wife Olga, who had cancer and was in a wheelchair after a stroke. After an operation to cure a duodenal ulcer, Picasso left his Paris surgeon a blank cheque to overhaul the operating theatre and another to repaint the surgery section.

He was both protective and generous towards Jacqueline. When he asked her to marry him, he warned her about the possible conflicts that lay ahead given his wealth: “If one day I fall ill, the others won’t let you care for me.” In their first months of living together, he banned her from speaking to visitors unless he signalled that she could. He argued it was the only way to prevent acquaintances speaking ill of her: a beautiful young divorcée was sure to cause envy. “I’d stay as dumb as a carp. I played the role of the perfect idiot,” she said. But he bought both the castle and the mansion under Jacqueline’s name.

Little could have prepared Jacqueline for the infighting that followed when Picasso fell ill in old age, with heart problems and breathing difficulties. Claude and Paloma, whom she had befriended, turned against her, accusing her of holding their father hostage. They sent bailiffs to the mansion to register this. From his bed, Picasso shouted to Jacqueline: “Throw them out. Let them go to the devil!” Three of Picasso’s children – including Paulo, his son by Olga – sued him in an attempt to ensure they inherited his fortune. Under the law of the time, they stood to inherit nothing, as they were illegitimate; they insisted that Picasso draw up a will in their favour. He refused and the children lost the case. After consulting Jacqueline, he decided never to see them again. He remarked: “If I’d known how things would turn out with my children, I’d have done better to piss against a street light.”

But the attacks from his family fuelled the artist’s work. “It was a formidable outlet,” Jacqueline recalled. “He’d go into his studio and come out liberated, purified of everything.”

During the last two years of Picasso’s life, she was at his bedside day and night. “There were times when Jacqueline drank enormously. She was affected not only by seeing her husband dying, but also by her difficult relations with her daughter, Cathy, and the fact that her former father-in-law was dying of cancer. She felt alone,” said Dupont. She became yet more depressed when both her father-in-law by her first marriage and her doctor, both of whom she was very close to, died soon after each other.

In April 1973, on the eve of his death, Picasso drank some herbal tea, as every evening, and then stood looking at himself in a mirror. He said to Jacqueline: “Have I got enough canvases and paintbrushes? Tomorrow I’m going to start painting.” The following day, shortly before noon, as a doctor gave him injections to help him breathe, Picasso asked him if he was married. The doctor replied that he wasn’t. “You’ve made a mistake; it’s useful. You should,” Picasso said. He then turned to Jacqueline, who was holding his hand, and whispered: “My wife, it’s marvellous.” They were his last words. Jacqueline said of what followed: “I saw a pink face become grey, and I don’t accept it.” For six days and nights she watched over the coffin in the guardroom of Vauvenargues castle. She buried him in front of the grand staircase at the castle entrance.

Jacqueline was attacked for banning Picasso’s children from the funeral, except for his son Paulo – the only one who had maintained a relationship with him. In fact, according to Dupont, she was simply obeying instructions left by Picasso, who had never forgiven them for accusing her of kidnapping him or for suing him.

On the night of the funeral, Jacqueline, in her white nightdress, stretched out on the burial mound in the snow and slept all night there. In the seven-year war over Picasso’s legacy that followed – the law changed in 1975, giving rights to illegitimate children – Jacqueline requested that she be left with the portraits he painted of her, and the works he had dedicated and given to her. Lawyers and court-appointed experts descended on Picasso’s properties, labelling everything, down to his toothbrush and a bouquet of dried flowers sent by the musician Mstislav Rostropovich, which they believed was a work by Picasso. Whenever Jacqueline left the mansion, she was asked to empty her pockets.

One morning, a state-appointed receiver and his team entered her bedroom, turned her mattress over, checked under the bed and rifled through her knicker drawer. Later that day, an exasperated Jacqueline gently pushed a ceramic ashtray decorated by Picasso over the edge of a table, while looking the other way. The ashtray shattered as it hit the floor. “And one fewer number for the inventory!” she shouted as the experts cried out in horror. When the lawyers for Claude and Paloma asked for their father’s bed, she promptly burnt the mattress in the park outside the Notre-Dame de Vie mansion.

From now on, Jacqueline, who was left close to 1,000 works as her share of the colossal inheritance, fought to preserve and promote Picasso’s work. “She wanted all the works to be shown to the public; she said paintings weren’t for rich collectors. It was her obsession. And unlike other members of the family, she didn’t sell a single work,” says Dupont.

Three months after Picasso’s death, Jacqueline decided, in accord with his son Paulo, to push for the creation of the Picasso Museum in Paris. She spent three hours walking through her home to select works to donate to the museum. She also gave the Louvre Picasso’s personal collection of works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Renoir, Matisse, Miro and Modigliani, among others. When she lent works, she renounced all her rights over publication of images in postcards or posters, and demanded no fee for the loan. And she would pay for her own ticket to the exhibition. All she asked for were catalogues to give to friends.

Many friends and even chance acquaintances benefited from her generosity. When a young petrol-pump attendant admired her white Lincoln, she stepped out and handed the keys to him. “My husband’s dead. I don’t need it any more. It’s yours. I’ll take a taxi home,” she said.

But her husband’s death, and the war over the legacy, drove her to seek refuge in drink and sleeping pills. According to Dupont, Jacqueline had simply taken too many blows. The early loss of her own mother also weighed on Jacqueline, and she often spoke of her. When Jacqueline was depressed, she would knock on Dupont’s bedroom door in the night and say: “Come on, let’s go and see the paintings.” The two women would walk through the mansion, Jacqueline talking about how much she missed Picasso. “Pablo is waiting for me and I’m late,” she would say. Dupont only once dared to mention the alcoholism, telling Jacqueline: “I’m afraid for you. You have to be careful.” She shot back: “What do you mean?” Dupont replied: “I think you should stop. You scare me.” Jacqueline was so angered, she treated Dupont frostily for three months.

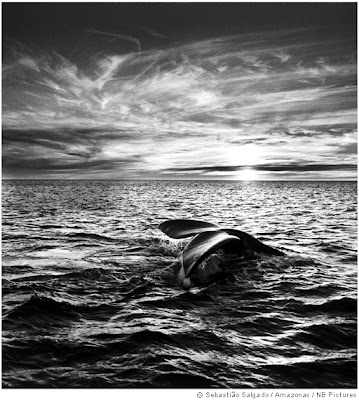

In September 1986, Dupont spent a week as a guest of Jacqueline. Over lunch in a Riviera restaurant, the frail Jacqueline kept staring out at the Mediterranean and repeating: “Pablo, why aren’t you here?” Dupont took her hand and tried to comfort her, but to no avail. Back at the mansion that evening, Jacqueline asked Dupont to stay and become her assistant, to help run her affairs and organise exhibitions. Dupont refused, saying she wanted to remain a journalist. Dupont spoke to Jacqueline for the last time two weeks later, on October 13. Again and again, Jacqueline asked her: “Do you love me?” Again and again, Dupont said yes, Jacqueline was her friend. Jacqueline suddenly said: “So now I can hang up.”

The next morning, Jacqueline asked Doris, her housekeeper, to prepare Dupont’s bedroom and put fresh flowers there. “Why? Is Pepita coming?” asked Doris. “Yes, very soon,” Jacqueline replied. In fact, Dupont had made no plans for returning. That evening, Jacqueline told Doris she was going somewhere “where you cannot come with me”. She said Doris would live in her seaside flat in Cannes from now on, and gave her a wad of banknotes worth £20,000.

Around 3am on October 15, as she lay in her bed under a blanket like the one she had covered Picasso with at his death, Jacqueline pressed a revolver she kept in a drawer of her bedside table to her right temple and pulled the trigger. Doris found her body at breakfast time.

“I didn’t see it coming,” says Dupont. “And yet Jacqueline told me sometimes that she wanted to end it all. But she looked so happy organising exhibitions and making gifts to museums. Jacqueline’s tragedy is that she couldn’t trust anyone. Everyone who entered the gates of Notre-Dame de Vie came to beg for something.”

There are two enigmas for Dupont. Firstly, Jacqueline told friends and acquaintances that she wanted 61 works she had lent to an exhibition in Madrid to be given to Spain, but the wish was flouted and the works returned to France. Secondly, Jacqueline told Dupont several times that she had written a will, but her solicitor said he never saw one and it has not been found.

Nor have Jacqueline’s last wishes for her homes yet come true. She wanted the mansion at Notre-Dame de Vie to become an old people’s home, or a home for the destitute, but the property, still crammed with Picasso’s archives, is regularly put up for sale by her daughter. It has yet to find a buyer. Jacqueline wanted the castle at Vauvenargues to become a museum. Her daughter has recently announced that this would happen in 2009 – 23 years after Jacqueline’s death.

One of Jacqueline’s few last wishes to be respected was that she be buried, in a Spanish black cape like Picasso, in the vault next to him in front of the castle. She had once told Dupont: “I’d like to be wrapped in Pablo’s last canvas.”